Paricutín erupting, by Dr. Atl by Philip Hall I married into a large and regionally important Mexican family, and so got to know some parts of Mexico quite well. I lived there, first as a student at the university of Vera Cruz in the early eighties, later in Mexico City…

Category: Mexico

Now, the USA must court Mexico and shower it with gifts and apologies

The USA must stop trying to dominate the world and instead form stronger, healthier ties with its southern neighbour by Phil Hall After the fall of the perfect dictatorship of the PRI in 2000, a progressive conservative came to power in Mexico called Vicente Fox. His rise to power was…

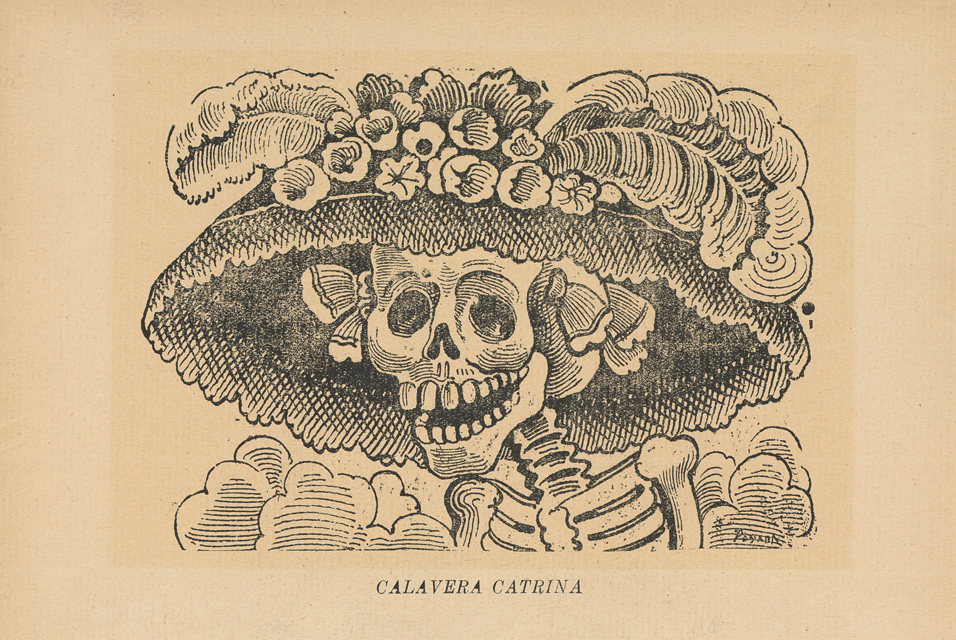

How to celebrate the Day of the Dead

… and a calavera for the selfish By Phil Hall So you have lived deep and extracted all the sweetness out of life, and you have had your last meal. But, what food and drink would you like people to remember you by? What wafting smell would have the power to…

My journey to the end of the world

By Phil Hall For most of the journey I was slap up against a secretary from Mexico City. It was a cramped 36 hour drive. When we got there Julie and I walked, slowly unfolding, heading towards the cheap hotel in the dark. It was 2 am. We could hear…

British Artists in Mexico

England is, as far as colours go, fairly subdued and uniform. Mexico is the opposite By Simon Brewster Although I have lived and worked in Mexico for almost 40 years, my first impressions of the country are still very vivid. After landing in Mexico after a stopover in the Bahamas,…

The Poetry of Markets

The highest Mexican poetic sentiment, higher than all the others, was the symbol of flowering. By Phil Hall One of the greatest pleasures in my grandfather’s life was to visit the market in Cannes, to admire the variety and quality of the produce on offer and to chat to some…

You must be logged in to post a comment.