Men of the London Rifle Brigade with troops of the 104th and 106th Saxon Regiments, IWM Why do socialists defend bourgeois nationalism? by Philip R. Hall This was the key document of all the anti-colonial movements: ‘Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism’ by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. Whatever else was written…

The Hideous Strength of the Highwayman

The widening of the highways is a modern form of enclosure and land theft to benefit the wealthy by Philip Hall You put your life in danger if you walk along A roads and country lanes in the United Kingdom, despite the best efforts of the glorious Ramblers Association, which…

The Cemetery for Amateurs

Harry Greenberg There is, somewhere in Prague, a most peculiar cemetery – I cannot say where, for I was taken there by car when fog lay over the city like a fetid blanket. It’s for musicians. But not any musicians. Only amateur musicians who have played in an amateur symphony…

An interview with the new AI Chatbot tool and corporate, behavioural engineer, Bing

The Bing Chatbot, prompted by Phil Hall ‘The construction of meaning is a source of joy for me.‘ by Phil Hall My first impressions were not good. The chatbot immediately obscured a historical fact: CIA involvement in the death of Patrice Lumumba. No African, European, American or Asian child trying…

An Open Letter to the Aliens

Have done with it! Show yourselves! by Philip Hall Have done with it! Show yourselves!You are hiding something. You are behaving in a way that we find very suspicious; like a leopard or a human predator waiting in the shadows, kidnapping people. You moon people on lonely highways like annoying…

Curing the Pig, by Eliza Granville

Episode 10 The Quixotesque misadventures of unreconstructed Marcher Morgan Jones-Jones, who has probably not heard of the suffragettes let alone second- and third-wave feminists. “Give it a rest, can’t you?” snarled Morgan, his eyes scanning the green for a large stone to dash the creature’s brains in. He didn’t feel…

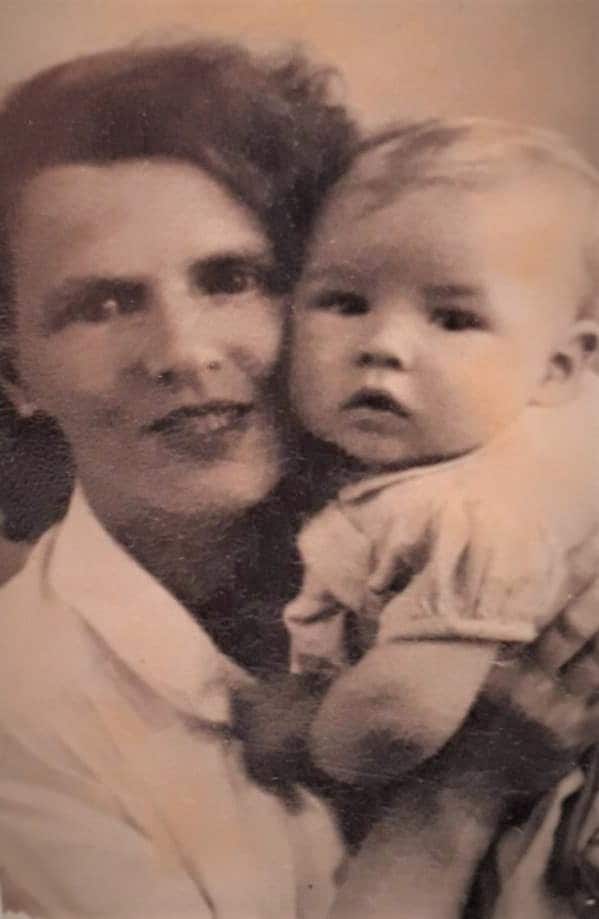

1. Isobal and Henry

Picture of Isobel and Joseph by Margaret Yip I was born in the middle of Clement Attlee’s term as prime minister in 1949. I was the fourth child born to my parents. My mother, Isobal, had been in service before marriage, and my father, Henry, was a miner. After my…

Now, the USA must court Mexico and shower it with gifts and apologies

The USA must stop trying to dominate the world and instead form stronger, healthier ties with its southern neighbour by Phil Hall After the fall of the perfect dictatorship of the PRI in 2000, a progressive conservative came to power in Mexico called Vicente Fox. His rise to power was…

The right to property must not be inalienable*

Government limitation and enforcement of the duties of property ownership is one of the foundation stones of a good society, not an economic lever. by Phil Hall Rather than imagining they are powerful citizens, the ultra rich prefer to believe that they are naturally unconstrained and owe little to individual states. They…

Vampire AI wants your mind juice

AI is the new Juju of the Ruling Class by Phil Hall AI is a new curtain the ruling class would like to hide behind; it is their juju, their voodoo, their megaphone. AI technology is a development of that old machine that used to trigger automatically with an audible…

Discourse on the Logos

Reason without love and the imagination is a curse by Phil Hall In trying to understand the concept of the Logos I read how Pope Benedict described Christianity as the religion of the logos. ‘From the beginning, Christianity has understood itself as the religion of the Logos, as the religion…

Perspectives on Eichmann: Explaining Perpetrator Behaviour, by Andrew Elsby

Review by Arjay Frank Otto Adolf Eichmann (1906–62) has been the subject of a surprising number of studies, given that he was merely a middle-ranking officer in the Schutzstaffel (SS) – a lieutenant-colonel, in fact – and, as such, was responsible for carrying out the orders of others, and would…

Con’s Shakespearean Garden

Visits to the Merlin of Coombe Hill By Phil Hall Con lives in the house he was born into more than 60 years ago. Everyone notices it from the street; partly because it looks run down and partly because there are sometimes cats in the front garden. One of the…

Calaverita

Death came today and gave me some adviceShe said; ‘Good news: I’ve designed a special diet for you.If you follow my instructionsTwo years from now you’ll be as thin as I am.After all, isn’t your health the most important thing?And your own happiness must be your prime concern.If you know…

Editorial: Stop this Madness!

Stop the war in the Ukraine! ‘Do you know what I do to people who get in the way of me?’ asked the thuggish manager of a GAZOPROM plant sitting across the table from me. ‘No, what do you do to them?’ ‘I destroy them,’ He said. And he stared…

US and European drug consumers are the real ‘bad hombres’: they generate the trade and cause the deaths

By Phil Hall Again and again, it needs to be reiterated. Mexico’s war against the drug traffickers is mainly a US war. If Mexico has failed to defeat the drug traffickers on one side of the border, then the US has failed to defeat it on the other side of…

Hurrah for muscular secularism!

Letter from an Ex Sheikh I have always used pseudonyms when participating in online debates. Most of these debates are on sociopolitical matters in Chad and in the Middle East. Not being able to speak French and the high rates of illiteracy in Chad, mean that a large chunk of my…

Cruelty to Boys in Afghan Schools

By Asad Karimi In Afghanistan, while girls have their right to education stripped from them, boys at schools in the countryside are victims of harsh treatment and abuse. Asad Karimi writes about his experience. When I was in Afghanistan and I was six or seven years old, I didn’t like…

Curing the Pig, by Eliza Granville

Episode 9 The Quixotesque misadventures of unreconstructed Marcher Morgan Jones-Jones, who has probably not heard of the suffragettes let alone second- and third-wave feminists. The visible universe could lie on a membrane floating within a higher-dimensional space. The extra dimensions would help unify the forces of nature and could contain…

Fiji’s Half Century of Independence

By Émile St Clair Fijians on 10 October 2022 celebrated their National Day, and looked forward to the 2022 general election, whose exact date at that time was yet to be announced. Fiji Day prompted at least two high-profile articles in Fiji’s national press, those of Mahendra Chaudhry and Dr…

Tagore Prize 2021-22 Awarded to Sudeep Sen

Review by Peter Cowlam All of us here at Ars Notoria are delighted at the news that our poetry editor, Sudeep Sen, has been awarded the prestigious Tagore Prize for 2021–22. The Rabindranath Tagore Literary Prize, a literary honour in India conferred annually for published works by Indian authors, recognises…

The Tragedy of Mister Morn, a Play by Vladimir Nabokov

Review by Peter Cowlam Nabokov, an aristocrat dispossessed by the October Revolution, in what is typical for him applies aesthetics rather than political discourse as filter over the coup Mister Morn has successfully repelled. The distortions of social unease are just a spectre to be poeticised over. It is Morn,…

Curing the Pig, by Eliza Granville

Episode 8 The Quixotesque misadventures of unreconstructed Marcher Morgan Jones-Jones, who has probably not heard of the suffragettes let alone second- and third-wave feminists. When seven long years had come and fled; When grief was calm, and hope was dead; When scarce was remember’d Kilmeny’s name, Late, late in a…

Depression # 32 by Dan Pearce

Dan Pearce has done editorial work for many magazines and newspapers including New Society, Honey, 19, Oz, The Observer, The Times and Sunday Times, Mayfair and Penthouse. Dan has created book and record covers, political cartoons, comic strips and caricatures and he has written two graphic novels: ‘Critical Mess’ (against the nuclear industry)…

A rat race is for rats. We are not rats.

Jimmy Reid’s 1972 speech on alienation . ALIENATION is the precise and correctly applied word for describing the major social problem in Britain today. People feel alienated by society. In some intellectual circles, it is treated almost as a new phenomenon. It has, however, been with us for years. What…

Hamba kahle, Harry.

HAROLD VOIGT, SOUTH AFRICAN PAINTER 1st May 1939 – 9th October 2022 by Leigh Voigt How does one give an unbiased, honest appraisal of one’s own husband and have the gall to call it an obituary? Does one resort to clichés? Borrow words from the pens of others? No, one…

Photographs through an art filter

Experiments with photo art applications, in particular the PRISMA application. by Philip Hall Passing photos through ready-made filters hasn’t really taught me much about how paintings and drawings are made, but doing this for a decade has taught me how important it is to have an artist’s eye and how…

King Charles III’s Sacred Task: dissolve the institution of Monarchy

Bring the powerful to heel, don’t glorify monarchs and privilege by Philip Hall The idea that Charles III is divinely appointed to rule over us is ridiculous! Yet, ultimately, it is the metaphysical idea of the divine right of kings that gives King Charles III his legitimacy as the head…

The Alphabets of Latin America: A Carnival of Poems, by Abhay K

Reviewed by Inderjeet Mani Latin America can lay claim to some of the world’s most magnificent geographies and vital ecosystems, teeming with unique life-forms and vibrant subcultures. The area has also borne witness to vast empires and savage colonial histories, and fired the imaginations of many gifted writers and artists….

Curing the Pig, by Eliza Granville

Episode 7 The Quixotesque misadventures of unreconstructed Marcher Morgan Jones-Jones, who has probably not heard of the suffragettes let alone second- and third-wave feminists. That’s the thing about people from the Welsh Marches, we All-Wise Three have observed, they’re neither one thing nor the other – and sometimes they’re both….

Nothing Stays Put, by Harry Greenberg

Nothing Stays Put The strange and wonderful are too much with us. The protea of the antipodes – a great, globed, blazing honeybee of a bloom – for sale in the supermarket! We are in our decadence, we are not entitled. What have we done to deserve all the produce…

Obituary: Bryan Greetham, teacher, writer and thinker

By Pat Rowe Bryan Greetham (1946-2022) the writer and thinker, died on Sunday 26th June in Estepona, Spain. Above all, Bryan wanted to help students of all ages be the best thinkers possible. Bryan was born in Faversham, Kent. He failed the 11 plus exam and went to a secondary…

Six Poems by Peter Adair

London, 1983 O I had a future. Patrick Kavanagh Once there was a bedsit the size of a coffin. Once there was a man pounding out on his typewriter short stories that never made the classic Irish canon. The inmates twist and turn on their celibate beds. Each avoids the…

Curing the Pig, by Eliza Granville

Episode 6 The Quixotesque misadventures of unreconstructed Marcher Morgan Jones-Jones, who has probably not heard of the suffragettes let alone second- and third-wave feminists. What happened now Mam was gone? Without that huge and slippery post over which he had for so long vainly tried to throw his tiny mooring…

Three poems by Dominic Fisher

We are pleased to publish three poems from Dominic Fisher’s latest collection of poems, A Customised Selection of Fireworks, available from Shoestring Press later this month (May 2022). A Customised Selection of Fireworks It’s the sequence that really matters colour rhythm flow which isn’t something the lay person gets right…

The Best Asian Poetry 2021–22 (editor Sudeep Sen)

review by Peter Cowlam Kitaab International is a Singapore-based publishing house, whose open call through various media outlets across the world, when the anthology was planned, resulted in 1,500 pages of poetry sent in by almost 500 poets. As commissioning editor, Sudeep Sen invited further writers from across ‘AustralAsia’ to…

RABINDRANATH TAGORE AS THE INTIMATE ‘OTHER’

SUDEEP SEN 1. RABINDRANATH TAGOREhaiku triptych ERASURE lines of poems scratched out, erased to ink in — new shapes — art revealed SELF-PORTRAIT gouache shade’s matt-blur — an outline of the psyche — subtle peek into soul’s eye SONG rabindra sangeet’s nasal baritone — honey- tinged, monotonic — Sudeep Sen…

The Labyrinths of Time

by Peter Cowlam A marine organism in unfathomable ocean depths receives light from a star a light year away, and responds, with a tiny twitch, the merest throb. By definition, the light the organism is influenced by has taken a year to reach it, as a staggered simultaneity, asking us…

ALFREDO PÉREZ ALENCART

WPP [World Poetry/Prose Portfolio] New Series | No. 1 ALFREDO PÉREZ ALENCART, born in Puerto Maldonado, Perú in 1962 is a Peruvian-Spanish poet and teacher at the University of Salamanca. He has published 15 books, among them, Mother Forest (2002), Hear me, my Brethren (2009), Cartography of the Revelations (2011),…

Coarse Art

By Paul Halas The democratisation of the image Art is everywhere, whether it’s highbrow gallery art, pulp, throwaway art, or the vast array of moving images available to us. Perhaps because my parents excelled in the production of animated films – possessing talents I sadly didn’t inherit – I was…

You must be logged in to post a comment.