The Jevons Paradox from Gaia, Sixth Extinction Series by Gordon Lidl The Jevons Paradox, Marx, the Modern Left, Deep Greens, AI and Collapse. by Gordon Lidl I want to tell you a story about a painting, a large painting I finished two years ago as part of a series of…

7. Never Again!

by David Yip At home, my younger sister, Diane, is working in Leeds and spends a lot of time there, staying in hotels. She tells me that she will be moving there as it makes more sense, but she needs to sell her houses. She asks if I will buy…

ANANYA VAJPEYI

Ananya Vajpeyi. Original photograph Gautam Menon From Place: Intimate Encounters with Cities Ananya Vajpeyi is a Professor at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, New Delhi. An intellectual historian, political theorist and writer, she was educated in Delhi, Oxford, and Chicago. Her book, Righteous Republic: The Political Foundations…

Geo Milev: PROSE POEMS

Bulgarian poet Geo Milev (1895-1925). Photographer unknown Introduced & Translated from the Bulgarian into English by Tom Phillips Geo Milev (1895-1925) was a poet, translator, critic, editor and activist who introduced a radical modernist strain into Bulgarian literature. Equally radical in his politics, he was extra-judicially executed during a round-up of communist…

Beena Kamlani: Excerpt from The English Problem

Beena Kamlani. Photograph Beena Kalmani Beena Kamlani’s debut novel, The English Problem, was published in January 2025 in the U.S. by Penguin Random House and launched in India at the Jaipur Literary Festival in January 2026. The Indian edition has just come out from The Bombay Circle Press. Her short…

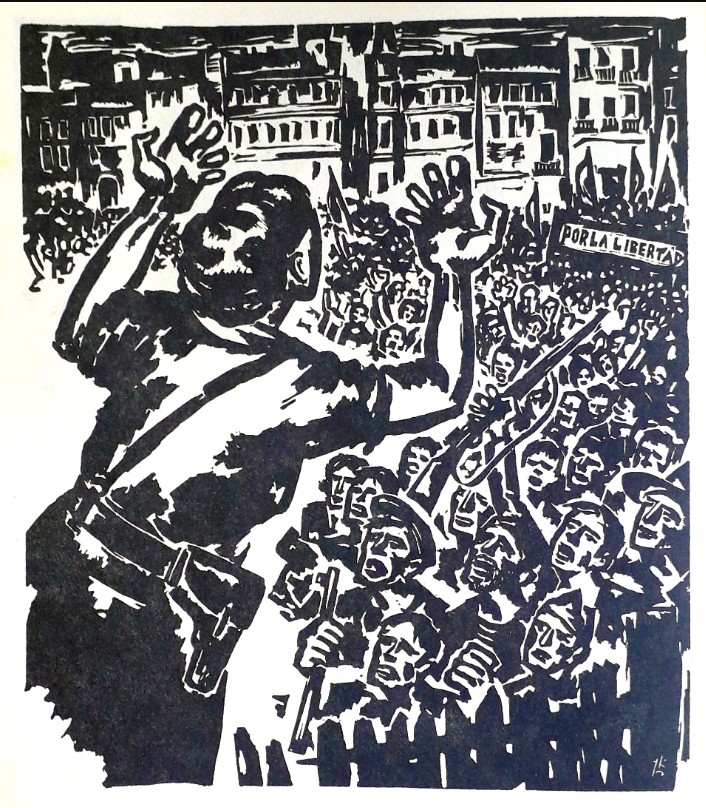

A Letter to the Apolitical You, Rudi

Đorđe Andrejević Kun – Pasionaria speaks to the fighters before going to the front. Wikimedia Commons A response to a friend’s remark that ‘Lots of people have an aversion to politics.’ By Phil Hall First, we need to define the word politics. It is a set of activities associated with making…

In Translation: TWO of Ewa Lipska’s FURTEEN TALES

Illustration ©Sebastian Kudas Ewa Lipska (b. 1945) is one of Poland’s most eminent poets, a defining voice of the Polish New Wave (Generation of ’68) since her debut in 1967. Her work, translated into over a dozen languages including English, has earned her international stature and numerous awards, among them…

The Racial Resentment of the White Caliban

President Lyndon B. Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 on July 2, 1964. Photograph Cecil Stoughton, White House Press Office. Public Domain As wicked dew as e’er my mother brush’dWith raven’s feather from unwholesome fenDrop on you both! a south-west blow on yeAnd blister you all o’er! Caliban, The Tempest by Dustin…

Gustavo Gac-Artigas in Translation

Gustavo and Priscilla Gac-Artigas. Credit Priscilla Gac-Artigas Born in Santiago de Chile in 1944, Gustavo Gac-Artigas is a Chilean poet, novelist, playwright, and former political prisoner whose writing has long engaged with questions of memory, exile, testimony, and the ethical responsibilities involved in using language. Following the 1973 military coup,…

16. Little Tramp / Rich Man

Charles Chaplain as a young man Charlie Chaplin & Stan Laurel Norman B. Schwartz In September 1910, one of England’s most popular Music Hall acts, Fred Karno Company of Clowns, set off by ship to begin a scheduled tour of North America that would last twenty-one months. On board, there…

Solaris and the Loving Sky

Hari leans over to kiss Kris Kelvin. Screen Capture Mosfilm Fair Use by Phil Hall After Jules Verne, H. P. Lovecraft, Jack London, and H. G. Wells came huge advances in science and two horrifying world wars that exceeded all imagination in technology, horror, and human beastliness. In the post-war…

A Critique of Noam Chomsky’s Work

Noam Chomsky. Photograph April 1961 The Technology Review, MIT, Wikimedia Commons In both areas, linguistics and politics, Chomsky’s foundational hypotheses were inadequate. by Phil Hall My perspective on Noam Chomsky is informed by my background: a life lived across multiple countries and languages, an academic grounding in Russian and Spanish…

Ajay Jain: Extracts from ‘Charlie’s Boys’

Ajay Jain. Photograph Ajay Jain Sapere Aude, Sincere et Constanter Ajay Jain is a writer, photographer, and traveller. He has written sixteen books across genres including travel, business, fiction and memoir. He also runs Kunzum, an independent bookstore in New Delhi. He holds degrees in mechanical engineering, business management and…

S B EASWARAN: Five Poems

S.B. Easwaran, a former journalist who has worked in Gujarat and New Delhi, now lives in Sakyong, a small village in the eastern Himalayas. His poems have appeared in Prosopisia (an Indo-Australian journal), Interlitq, Drunk Monkeys, and Prometheus Dreaming. Sudeep Sen Secretsfor David Lynch (1946-2025) A speckled monarch reverses into…

The Road to Greater Khorasan

US Defeat in Iran will lead to the unification of the Persian-Sphere by Richard Steinhardt Let us set aside, now and forever, the ridiculous idea of a Greater Israel. The United States and Europe are not powerful enough to colonise more of North Africa and West Asia or eliminate its…

Mountain Wedding

Himalayan view. Photograph Sudeep Sen by Sudeep Sen It was good to wake up to the silence of the Himalayas this morning. The shifting grey palette of the clouds was an antithesis to the recent tsunami of stimuli. The pleated, opalus ridges hid their pine-green veneer in obfuscating skies. The…

A SPINNING COIN OF DHŪRTĀKHYĀNA

It did not spin like a normal coin, losing energy to the friction of the wood. It spun with a velocity that defied Newtonian physics, gaining momentum from the very air it displaced. Illustration WordPress by Yogesh Patel The penthouse was less a residence than a vaulted reliquary, a glass-and-steel carbuncle grafted onto…

Meeting Heiko Khoo

Heiko Khoo’s Karl Marx Walking Tours. Photo credit Heiko Khoo ‘For me, the key question is to reinvigorate a culture of discussion and debate’ Interviewed conducted by Phil Hall, Paul Halas and Gordon Lidl Phil Hall: Hi, Heiko. Thank you for joining us. How are you doing? Heiko Khoo: I’m very well,…

COLOUR, MOVEMENT AND BALLET

Bing Shi at the Drawn to Dance Exhibition in the Gallery of Royal Birmingham Society of Artists (RBSA) Gallery The artist Bing Shi in conversation with Paul Halas, Ars Notoria’s Art & Lifestyle Editor, and Phil Hall Paul Halas: This is our second meeting. Our first was two years ago,…

The Voltage of Fresh: Why Fruit Needs Fire

Roadside mango Snack in Mexico. Photograph Miguel González Freshness without friction is boring by Arun Kapil Manek Chowk doesn’t ease into the day. It detonates. Heat rises off cobbled stone. Diesel coughs. Metal shutters slam open. Somewhere behind you, something is already frying. In front of you, fruit – piled…

The Ramleh Tram Carries the Lifeblood of Alexandria

Alexandrian Tramway in the Rain. Photograph Mohamed Hozyen Ahmed, Public Domain By Adel Darwish Founded by Alexander and once governed by Cleopatra, Alexandria became a beacon of learning and cosmopolitan exchange. Today, in the name of development, the city’s physical memory is being dismantled — and the Ramleh tram is…

The Continuing US Attack on Indian Non-Alignment

S Jaishankar in Vienna (2023). Photograph Dean Calma / IAEA, Wikimedia Commons “We are very much wedded to strategic autonomy because it’s very much a part of our history and our evolution. It’s something which is very deep, and it’s something which cuts across the political spectrum as well.” —…

The Mysterious Death Wish of the Western Ruling Class

The USA and Iran at High Noon Will Lindsey Graham Get His Rocks Off? by Richard Steinhardt What would unleashing a war against Iran do? It would be a tremendous act of self-mutilation. The arteries of global energy trade would narrow and launch the Western economic system into a severe…

Don’t go to war with Iran, USA

The beautifully pedestrianised centre of Abingdon in 1969. Thank you town planners. Photograph Tony Hall This horrific geopolitical act would plunge us back in time to Abingdon in the late 1960s By Richard Steinhardt If the USA attacks Iran, Iran will destroy the oil installations in the Arabian Gulf and…

Geronimo!

An Amexican Quilt. Generated by WordPress The Coming Break up of the USA by Phil Hall Mexico, not the UK, not Canada, not Germany, not China, is the USA’s most important partner: its most important trading partner to the fertile south with a border thousands of kilometres long. And 50%…

DUSTIN PICKERING

Dustin Pickering. Photograph by permission of the author Sheaf of Weeping Be still my raven with beating wingslest the ashes of solitude value the clustersof unbecoming.I am taken by lackluster jewelsunder the sands of rumor.Your eyes will hide the livid saint. * The leaves broken in the nightwith ink-ridden hands,trusted…

ARJUN RAINA: extracts from The Eye of Childhood

Not all brains work perfectly and survive life’s turbulent journey. Photograph by Amel Uzunovic The Brain Dear Reader Have you ever thought about your own brain, this mysterious organ, controlling all your actions, intentions, emotions, memories and feelings? Sitting up there in your skull, working to make your legs walk,…

READING THE PAPERS

by Roger Murphy He watched the story unfold in the papers. The first report appeared the day after he arrived, the last just as he left. The whole tragedy spanned the two weeks he spent in Cork, sorting through his mother’s effects and tying up the loose ends of her…

1. NEW MALDEN WRITERS: Rising Stars

As you get on the bus, there is no fuss. A seat with priority is there. Photograph Phil Hall Poems by John Grant I Do Like a Ham Sandwich I do like a ham sandwich with slices of tomato, But a sandwich of roast chicken, no stuffing.That’s the way to…

THE NATIONAL ELF

by John Grant I’m a little gnomeSitting on a stoneWaiting for the national elf to phone.“I am the most important national elf!There is no one more important than myself.But I have a little problem that is quite upsetting my life.Someone broke into the palace;Stole off with my fairy wife.“My elfin…

You must be logged in to post a comment.